Happy Russian Christmas. If that's what you're into.

Growing up, I preferred non-Russian Christmas. For me, it was all about Rudolph, Charlie Brown, Frosty the Snowman, and nostalgic commercials from the fine folks at Folgers and McDonalds. I'm nothing if not all American; I devour shared anticipation, brand names, and Groupthink.

Russian Christmas was always so anti-climactic when it'd limp along two weeks after school started. The songs, the characters, the decorations—everything was darker, more melancholy, and foreign. Santa was always the most medieval dude you've ever seen, and most annoyingly, it didn't warrant another school vacation. It was just some random Sunday in January consisting of a "Children's Festival" held in the basement of an Orthodox church, always headlined by some exhausted, bearded priest dourly beseeching, "Every child to get in line for presents now!"

I've always had a profound disconnect when it comes to Russian culture. Even as a child, I never felt more lost than when it came to their cartoon characters. I dug snarky, relatively modern, untraditionally irreverent kids and/or anthropomorphized animals who chomped cigars, questioned authority, and could pull lit dynamite from their back pockets, or at least could nasally deliver a contemporarily meaningful sermon on the true meaning of Christmas. Russian cartoons were always about Victorian hedgehogs in lace dresses offering tea to foxes in corsets. Or something. Long story short, I could never fully jive with what (I was told) Russian children found whimsical.

With that attitude, I'd most likely be a profound disappointment to my Great-Aunt Yelena Aleksandrovna Vasilyeva (Васильева Елена Александровна). By all accounts, she was an expert in what Russian children find enchanting, and in enchanting Russian children. Easily my most noteworthy, accomplished, and arguably famous family member1, she was an acclaimed childrens' author, decorated Scout Master, and undercover rabbit. Yet, she she still found time to question her faith, marry and divorce Cossack soldiers, and hang out with archbishops and tiger hunters. She was nothing if not ambitious. Also, to paraphrase an old Irish proverb (or Mark Twain), she "never let truth get in the way of a good story."

Yelena was born on 11 May, 1906 in Ashgabat, Turkmenistan (or 24 May, depending on the calendar). Her father, Aleksander Vasilyev, was a chief executive officer of the China Eastern Railway. Yelena grew up in China, and was born to Lithuanian and Polish parents—so why she was born in Turkmenistan is something of a mystery. She may have been birthed on the road from Crimea to Manchuria. Or perhaps Aleksander was stationed in Central Asia in some professional capacity, perhaps on the Trans-Caspian Railway. Details are sketchy, but either way, Yelena arrived in Harbin, China at the age of six months.

From an early age, Yelena wrote poems and plays. She also displayed a pronounced independent streak, as well as an affinity for the outdoors. During her grade-school years, her favorite playmates were a pair of Polish kids from Saint Petersburg named Edik and Kazik Yanushevichi. They regaled her with tales of Cub Scout camps back home, where the forests were thick with adventurous pre-teens who spent all day helping one's neighbor while learning the art of self-sufficiency. Young Lenochka was smitten, and determined to be a scout. Unfortunately, there were no Russian Cub Scouts—only Polish ones. So, at age 10, she informed her father that she intended to go Catholic.

"It's that simple," she explained. "You convert to Catholicism, become a real Polka, and you're accepted right away."

This revelation really chapped Aleksander Vasilyev's hide, surprisingly (or not) considering his dubious background. According to family legend, Aleksander Vasilyev—the staunch, upper middle-class white émigré—was originally Aleksandras Vasiliauskas, a Lithuanian bookkeeper who'd changed his name to get a better job in Russia. Not much is known about the self-styled Aleksandras except that he married a woman who claimed to be a direct descendent of Petro Doroshenko (Cossack political and military leader and Hetman of Right-bank Ukraine) and supposedly became the Comptroller General of the Trans-Siberian Railway. Otherwise, the man is an enigma; he considered himself gentry, yet was born in Kovno2. He Russified himself mercilessly to give his kids a shot at a better life, and then along comes his first-born daughter, demanding to become a Polish Catholic. Needless to say, his response was a firm nyet.

Although Yelena was brutally forced to remain Orthodox, she eventually joined some Russian Scouts—and ran with an interesting crowd. Her best friends were two guys named Boris Andrianovich Dmitruk and Vasya Lvov. Boris went on to become the Chief of the Manchurian Department of the National Organization for Russian Scouts (NORS) before succumbing to Typhus in Shanghai. Little Vasya—or rather Vasily Vladimirovich Lvov—grew up to be better known as the late Archbishop Nathanael. So much for Yelena becoming a Catholic.

At age 22, Yelena quit the Scouts, and married a down-on-his-luck, partially disabled former military cadet named Valentin Valkov. You can read a rather brilliant Russian article detailing his life story here. A month after the wedding, Yelena bumped into an old Scout buddy on the street, and he offered her a gig as Commanding Officer. When she told Volkov, he was livid—and her elation was short-lived as, once again, some patriarchal traditionalist pissed on her parade. Her new husband issued an ultimatum: "It's either me, or the Scouts! Choose!" Yelena was heartbroken; she cried, she pleaded, she threw things. But Valkov was steadfast in his idea that a woman's place should be in a lackluster, under-decorated kitchen, sweating over hot piroskhi. This was the first of many fights, and the newlyweds separated three and half years later because, purportedly, "he drank and didn't want to work." Interestingly, they stayed legally married until the end of the 1930's. Yelena supported Valkov financially, and when his myriad ailments necessitated a move South, she introduced him to family friends (and Yul Brynner's cousins) Valery and Arseny Yankovsky, who owned and operated luxury game reserves in North Korea. As it turned out, killing big cats was just what the doctor ordered, and the disillusioned Valkov finally found a place to call home with his new best friends, the Yankovskys—where, hopefully, the women weren't crazy broads who pursued their own interests.

Not content to merely serve as a procurer of friends for her ex-husband, Yelena threw herself back into scouting. She also began inundating Harbin's main Russian newspaper, Rupor (Рупор), with unsolicited poems, stories, and illustrations—all ostensibly created by a rabbit named Yurka (Юрка). The editors liked what they saw, so they test-ran her work a few times on the children's page. Before long, the kids of Harbin were hooked, and the newspaper brought her on full-time.

Yelena completed her questionnaire in 1936. She lists her profession as journalist, and her dependent as her infirm, 83 year-old Polish Catholic grandmother, Franziszka Josifovna Doroshenko. As for political affiliations, she claims that she's a Monarchist with Crimean citizenship, and that she's "never had a Soviet passport, has never applied for one, and does not ever want one." She even organized a literary circle named after Alexander Suvorov, the Suvorov Literature and Arts Society of Russian Youth. For an alias, she lists Yurka.

Yurka the Rabbit ultimately got so popular that they spun him off into his own children's magazine, Lastochka (Ласточка) aka The Swallow. Although it didn't start out as Yurka's magazine, per se. The magazine had been around for decades, but was on the verge of folding when one of Rupor's editors, E.S. Kaufmann (Кауфман Евгений Самойлович), bought the rag for nothing and gave Yelena a salaried, in-house position.

The word on the street was, the current staff at Lastochka just couldn't connect with children. The serials were boring, the stories were stilted. Yelena initially produced work according to the terms laid out in her job description, but ever the rebel, she soon found her own style, and began to ignore the advice of senior writers. This led to clashes with the editors, but by all accounts, Yelena's contributions were something Lastochka hadn't been in a long time: fresh, witty, and real. Everyone loved Yurka, and the magazine experienced a resurgence in popularity. By 1942, she'd muscled her way up to managing editor, fired everyone but herself, and spent the next three years supplying all the content (stories, poems, illustrations). After a while, she didn't even bother submitting copy for Kaufmann's review—she'd just toss the printed magazine on Uncle Zhenya's desk and walk away.3

In 1939, she finally got around to divorcing Valentin Valkov—if only to subsequently marry someone with the last name Goffman. She even took on the Goffman (Гоффман) name professionally for a few years. Mr. Goffman was most likely a man named Alexander Leonidovich Goffman (Гоффман Александр Леонидович) whose father had been involved in the White Movement. Very little is known about this period of her life, but one thing's for sure: at some point he must've told her what to do, because she was divorced in 1961 when she arrived in the United States—bearing the Americanized name Helen Hoffman.

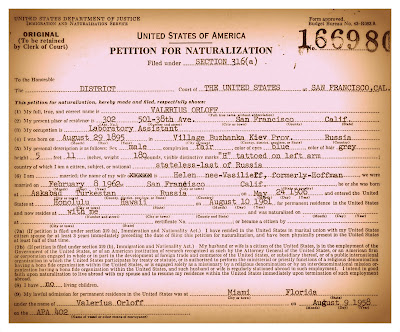

Yelena entered the United States at Honolulu, Hawaii on August 10, 1961 and settled in San Francisco. Unlike her brother and sister—whose Bay Area families had immigrated years before via Japan, or the Russian Settlement in the Philippines—Yurka was reportedly in Harbin until the bitter end. She'd even spent time training Soviet scouts. So much for being a Monarchist.

Our family knew her as Aunt Helen, a lovable old eccentric who wrote letters to Smokey the Bear, painted rabbits on pillowcases, and answered the phone, "Meow?" But she also stayed active in her Golden Years by self-publishing a children's magazine called "Scout" (Скаутёнок) that she cranked out entirely by herself, month after month, on a Xerox CEM machine. She also made a triumphant return to the world of Russian Scouting, and became something of a Bay Area luminary in that field.

Continuing to work well into the late 1970's, even after the doctor banned all activity due to heart disease, she said at the time, "I lived in the world to bring joy to Russian children. And for me it was also a great joy!" Supposedly, she was even overjoyed that her Americanized niece chose to give birth out-of-wedlock because "it was a clever way to make sure the Vasilyev name didn't die out."

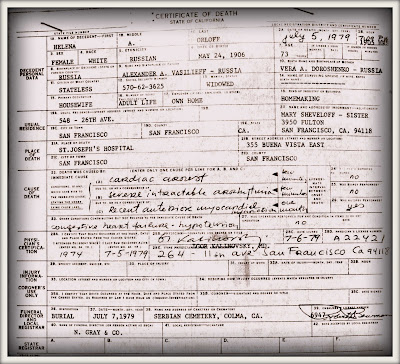

Unfortunately, Yurka died in San Francisco on July 7, 1979 (or fortunately, given the quality of life experienced by 112 year-old women these days). One of my earliest memories is attending her funeral. It was open-casket, and Yelena was dressed in a Scout uniform. Even as a three year-old child, I remember thinking she struck me as too youthful to have died from "old age."

Russian Christmas was always so anti-climactic when it'd limp along two weeks after school started. The songs, the characters, the decorations—everything was darker, more melancholy, and foreign. Santa was always the most medieval dude you've ever seen, and most annoyingly, it didn't warrant another school vacation. It was just some random Sunday in January consisting of a "Children's Festival" held in the basement of an Orthodox church, always headlined by some exhausted, bearded priest dourly beseeching, "Every child to get in line for presents now!"

I've always had a profound disconnect when it comes to Russian culture. Even as a child, I never felt more lost than when it came to their cartoon characters. I dug snarky, relatively modern, untraditionally irreverent kids and/or anthropomorphized animals who chomped cigars, questioned authority, and could pull lit dynamite from their back pockets, or at least could nasally deliver a contemporarily meaningful sermon on the true meaning of Christmas. Russian cartoons were always about Victorian hedgehogs in lace dresses offering tea to foxes in corsets. Or something. Long story short, I could never fully jive with what (I was told) Russian children found whimsical.

|

| Yelena Aleksandrovna Vasilyeva aka Yurka Circa 1930's Harbin, China |

"It's that simple," she explained. "You convert to Catholicism, become a real Polka, and you're accepted right away."

This revelation really chapped Aleksander Vasilyev's hide, surprisingly (or not) considering his dubious background. According to family legend, Aleksander Vasilyev—the staunch, upper middle-class white émigré—was originally Aleksandras Vasiliauskas, a Lithuanian bookkeeper who'd changed his name to get a better job in Russia. Not much is known about the self-styled Aleksandras except that he married a woman who claimed to be a direct descendent of Petro Doroshenko (Cossack political and military leader and Hetman of Right-bank Ukraine) and supposedly became the Comptroller General of the Trans-Siberian Railway. Otherwise, the man is an enigma; he considered himself gentry, yet was born in Kovno2. He Russified himself mercilessly to give his kids a shot at a better life, and then along comes his first-born daughter, demanding to become a Polish Catholic. Needless to say, his response was a firm nyet.

|

| Archbishop Nathaniel aka Vasya |

Shocked by her father's objection, Yelena argued that it was a non-issue because her grandmother was Catholic. Now allegedly, Yelena's mother, the stately Vera Vasilyev née Doroshenko, was Petro Doroshenko's sixth or seventh great-granddaughter through her father, a Crimean Cossack. Her mother, however, was a Polish Catholic named Franziszka. I guess Aleksander's mother-in-law didn't carry too much weight in the house, because when it came to his adolescent offspring worshipping the Pope, he flatly refused.

Although Yelena was brutally forced to remain Orthodox, she eventually joined some Russian Scouts—and ran with an interesting crowd. Her best friends were two guys named Boris Andrianovich Dmitruk and Vasya Lvov. Boris went on to become the Chief of the Manchurian Department of the National Organization for Russian Scouts (NORS) before succumbing to Typhus in Shanghai. Little Vasya—or rather Vasily Vladimirovich Lvov—grew up to be better known as the late Archbishop Nathanael. So much for Yelena becoming a Catholic.

|

| Valentin Valkov Circa 1936 |

|

| The Yankovskys Circa 1930's North Korea |

Not content to merely serve as a procurer of friends for her ex-husband, Yelena threw herself back into scouting. She also began inundating Harbin's main Russian newspaper, Rupor (Рупор), with unsolicited poems, stories, and illustrations—all ostensibly created by a rabbit named Yurka (Юрка). The editors liked what they saw, so they test-ran her work a few times on the children's page. Before long, the kids of Harbin were hooked, and the newspaper brought her on full-time.

|

| Yelena Vasilyeva (short and center) flanked by family and friends Circa 1937 Harbin, China (photo courtesy of Jorge Poulsen) |

In 1932, the Japanese invaded Manchuria, and the first thing they wanted to know was, "Who the hell are all these Russians, why are they here, and are they communists?" So the Bureau of Russian Emigrants in the Manchurian Empire (BREM, or БРЭМ) was born; an administrative division dedicated to "strengthening the material and legal situation of Russian emigrants residing in Manchukuo, establishing ties with the government of Manchukuo on all matters relating to emigrants, and assisting the Japanese administration in dealing with emigrant issues." Every Russian resident of Harbin was required to complete a lengthy, unwieldy census laid out like some unholy amalgamation of passport application, resume, and personality test. They're all still on file at the The State Archive of the Khabarovsk Territory.

Yelena completed her questionnaire in 1936. She lists her profession as journalist, and her dependent as her infirm, 83 year-old Polish Catholic grandmother, Franziszka Josifovna Doroshenko. As for political affiliations, she claims that she's a Monarchist with Crimean citizenship, and that she's "never had a Soviet passport, has never applied for one, and does not ever want one." She even organized a literary circle named after Alexander Suvorov, the Suvorov Literature and Arts Society of Russian Youth. For an alias, she lists Yurka.

In 1939, she finally got around to divorcing Valentin Valkov—if only to subsequently marry someone with the last name Goffman. She even took on the Goffman (Гоффман) name professionally for a few years. Mr. Goffman was most likely a man named Alexander Leonidovich Goffman (Гоффман Александр Леонидович) whose father had been involved in the White Movement. Very little is known about this period of her life, but one thing's for sure: at some point he must've told her what to do, because she was divorced in 1961 when she arrived in the United States—bearing the Americanized name Helen Hoffman.

Six months after arriving, she got married (for the third and final time) to a Ukrainian lab assistant named Valerius N. Orloff (b. 29 Aug 1895 - d. 6 Dec 1972). The only thing I know about Valerius is that Yelena outlived him. He was basically her Catherine Parr.

Our family knew her as Aunt Helen, a lovable old eccentric who wrote letters to Smokey the Bear, painted rabbits on pillowcases, and answered the phone, "Meow?" But she also stayed active in her Golden Years by self-publishing a children's magazine called "Scout" (Скаутёнок) that she cranked out entirely by herself, month after month, on a Xerox CEM machine. She also made a triumphant return to the world of Russian Scouting, and became something of a Bay Area luminary in that field.

Continuing to work well into the late 1970's, even after the doctor banned all activity due to heart disease, she said at the time, "I lived in the world to bring joy to Russian children. And for me it was also a great joy!" Supposedly, she was even overjoyed that her Americanized niece chose to give birth out-of-wedlock because "it was a clever way to make sure the Vasilyev name didn't die out."

1 Not counting Kylie Minogue. Aunt Kylie is my fifth cousin, twice removed, and you're seething with jealousy about it.↩

2 The fact that his hometown rhymed with Govno, the Russian word for shit, provided an endless source of amusement for my grandparents.↩3 It's interesting to note that her parents were largely out of the picture at this point. Today, the ultimate fate of Aleksandras Vasiliauskas and Vera Doroshsenko remains in a mystery. In the mid-1920's, an agreement was signed that only Soviet and Chinese citizens could be employed by the CEL. They may have gone back to the Soviet Union, or taken Chinese citizenship (as my grandfather, Yelena's brother had). Who knows? Nobody ever talked about them growing up, so they probably weren't a lot of fun. ↩